Manager Selection in Venture Capital

Backing Mean, rather than Median, Managers is Good Enough

The Power Law, popularized by investor Peter Thiel and then immortalized into the eponymous book title by author Sebastian Mallaby, drives venture capital returns. Venture capital empirically operates according to this principle, with singular outliers in most portfolios returning more capital than the entire portfolio’s remainder. Those VC managers who wish to outperform are therefore almost entirely beholden to not just the existence of the outlier they back, but to its scale and amplitude.

“The biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined. This implies two very strange rules for VCs. First, only invest in companies that have the potential to return the value of the entire fund. This is a scary rule, because it eliminates the vast majority of possible investments. (Even quite successful companies usually succeed on a more humble scale.) This leads to rule number two: because rule number one is so restrictive, there can’t be any other rules.” - Peter Thiel

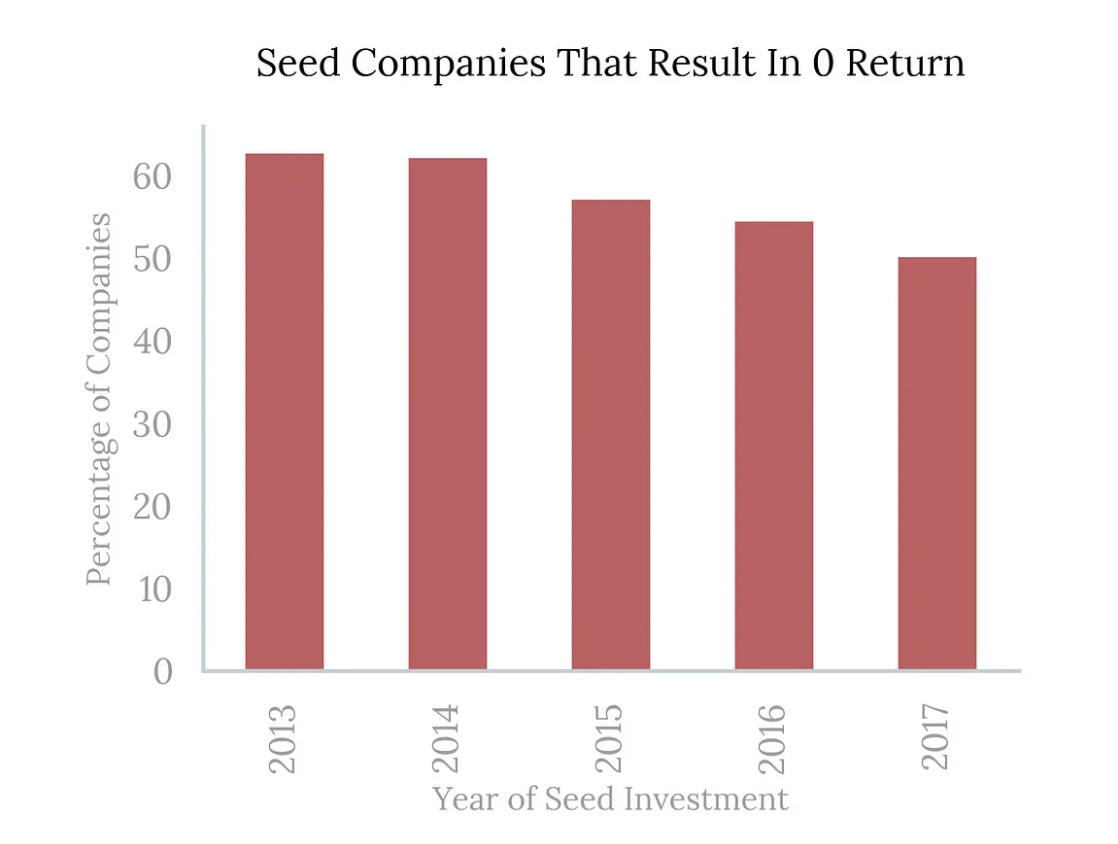

The other great truth, called out by Level Ventures’s Jake Kupperman in his comprehensive piece which we’ll further explore below is the notion from Michael Mauboussin that, “A lesson inherent in any probabilistic exercise: the frequency of correctness does not matter; it is the magnitude of correctness that matters.” In other words, even though many if not most of pre-seed investments will go to zero, the log-normal, or long tail distribution of outcomes means that Power Law, and the magnitude of that outlier, is really what matters in early-stage investing.

Pundits also point to the rising nominal interest rate environment and pose the rather drab and predictable question, “with risk-free returns going up, why would anyone invest in venture capital?” The answer I usually give first points out that the risk-free interest rate is actually the nominal rate minus the inflation premium, and at least based on my own experience of CPI it’s a rather glib figure that factors out the real costs of life in a policy-convenient way so as to hoodwink the majority. So the real risk free rate of return isn’t as large a plate of free lunch as one might think.

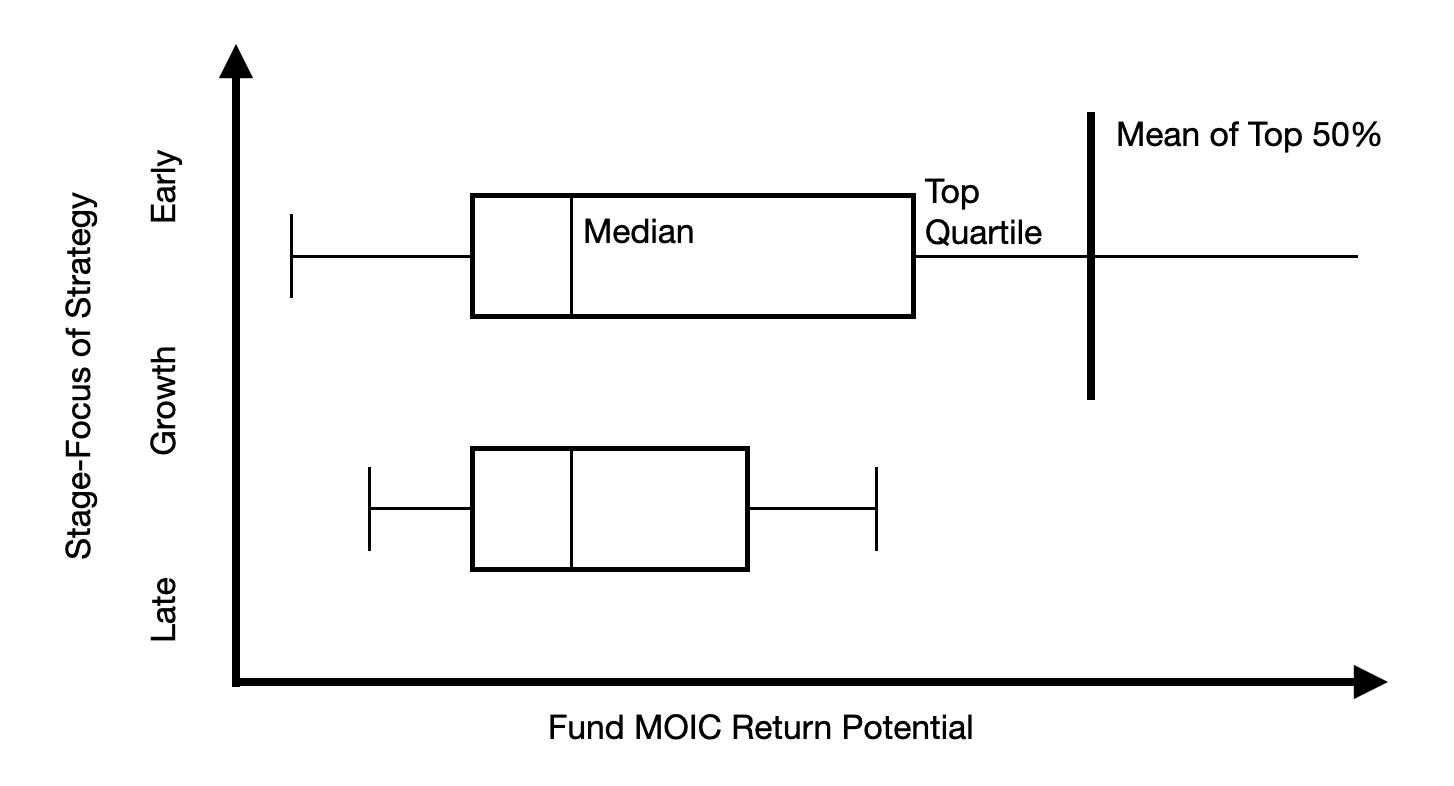

The second point I make is that there is very little dispersion in the risk-free rate of return, in other words mean and median are identical, but the dispersion in venture capital returns is massive. The difference between an under-performing and an over-performing VC manager can be significant. Moreover, the distribution of venture returns is not Gaussian or “Normal.” It’s positively skewed, with outlier managers significantly outperforming the median managers. In other words, the Mean performance is many levels higher than the Median performance in venture capital.

Abe Othman, head of Data Science at AngelList published a study in 2019 demonstrating that by making a higher (n) number of bets significantly increased the chance of getting mean, rather than median returns, in venture capital. So if you’re a manager trying to outperform, taking more shots on goal is an effective strategy. My co-founder Jenny Fielding and I have discussed this for years, and this is the reason why we’ve written one check every five days for the last half decade. This is a cadence that indexes around 8 percent of companies we’re introduced to by a founder in our community. We’ve invested about 400 times out of about 5,000 opportunities. You have a greater chance of finding a successful company, and the amplitude of that winner will determine the extent to which the Power Law holds true, with that one winner being more valuable than the remainder of your venture portfolio.

For LPs, particularly funds of funds backing numerous managers, they also focus on this notion of differentiating between Median and Mean managers. By looking at what differentiates a manager insofar as how they Source, Select, and Support, LPs can determine if a manager has some, or many, characteristics to outperform others. LPs need not have to predict the future of which managers will perform best; they simply need to back a portfolio of managers who have the right characteristics to outperform. Performance dispersion is so wide, and the positive skew so great that the Mean performance is multiples of the Median. In fact, Morgan Creek has done research that suggests that the mean performance of the Top 50% of venture funds exceeds the top-quartile of all VC funds. This again, is because of the skewness, and how much top performing managers outperform. The average of their performance is better than the bottom 75% of firms. The argument for “why invest in venture capital” is clear if LPs can identify a few key characteristics to identify and isolate better managers. Then they only need the average of those managers to outperform the top quartile of firms. And top quartile venture capital returns far outpace alternatives in equities or fixed income, making VC a worthy allocation strategy. Of course if you’re unable to access or select for outlier manager performance, you’re also probably better off consolidating your capital in asset classes barely-shielded from inflation. As with many things, it comes down manager selection access, process, and execution.

The team at Hummingbird VC have titled these fund outliers “nomads,” and built a fund of funds around it to target funds that look distinctly different. These are decidedly not your household names, because to find true alpha you need to be non-consensus, meaning you stick out. And you need to be correct. So outlier funds will, by definition, be the odd balls, those that come across as a bit strange. As entrepreneurs ourselves, the best fund managers probably won’t shy away from this. At Everywhere Ventures, for one, I heard a panelist recently state, “we would never back a global generalist pre-seed fund,” and the room broke into laughter. This is exactly what we do, and we’re not afraid to be contrarian. That statement didn’t make me question what we do; it bolstered my confidence because we have a model that uniquely allows us to do this unlike just about any other firm. This irreverence, and self-belief is what we look for in startup founders, and it’s certain to be a characteristic in nomadic, truly differentiated fund managers. Jordan Nel at Nomads and Hummingbird VC has written an excellent summary of this.

So if you’re a VC manager what should you do?

Focus on what differentiates you from other managers in how you Source, Select, and Support. This is how you can differentiate from the Median.

Your irreverence, your uniqueness, is your comparative advantage.

Make a high number of investments to maximize your chance of Power Law distributions whereby one investment is worth as much as the remainder. This statement itself is irreverent in a high ownership-consensus world.

Recognize that many early-stage bets won’t work out, but you’re trying to maximize the existence, and amplitude, of a few outliers.

And if you’re an asset manager or LP making fund investments?

Focus on trying to back truly unique managers, as they have a greater likelihood of being outliers in terms of performance. These are your nomads.

Data suggests that the highest returns are pre-seed and seed investments, and managers selecting from within this stage are most likely to outperform later stage and growth returns (as is a function of entry valuation). Moreover, emerging managers (on funds I or II, or consolidating managers on funds III or IV) tend to outperform, but it’s hard to select them from the nearly 3,000 funds that have been raised since 2018. As such backing funds of funds may be the best strategy rather than selecting managers yourself if you don’t truly have great access.

You don’t need to be able to control everything or predict the future. You simply need to be able to isolate and identify characteristics that differentiate.

Back a small basket of funds of funds with great access, or if you can go directly, build a portfolio of emerging managers taking novel approaches, and back a variety of strategies such as ownership heavy, or high volume portfolios. As suggested above, earlier-stage, and earlier-vintage managers generally perform better than higher AUM funds particularly after Fund V (just about when you know their name, and all your peers give you more confirmation bias). Again being both contrarian, not consensus, and right is how you make alpha.

The question of what characteristics drive alpha is well trodden, and Heather Hartnett, founder of Human Ventures, has done a good job laying it out in her recent Forbes piece on “alpha generators.” There are over 2,700 VC managers with under $100 million AUM, predominately focused on the early stage. Many of them are known as “emerging,” but she makes the point that these managers who have deep networks, access to accelerators, and a core proposition for why they are accretive to the industry, providing something different, might be better called “alpha generators.” After all, if LPs can identify such characteristics to select top half managers, because of the highly skewed distribution this fact alone will allow them to isolate and consistently achieve top quartile venture returns outperforming other asset classes.

For more astute thinking on this subject I’d recommend reading works by Morgan Creek, and particularly Frank Tanner. Morgan Creek has decades of venture capital fund of funds and asset management experience from across the endowment worlds of UNC Chapel Hill, Duke, Stanford, and the Kauffman Foundation. They are one of the pre-eminent voices on VC asset allocation and manager selection. Many thanks also to Kate Simpson at TrueBridge for helping me refine these ideas, Eric Woo at Revere for continuing to build community around emerging managers, as well as to Kelli Fontaine at Cendana Capital for our conversations on this at Collision 2023. This post also builds off the great research done by fund of funds investor Jake Kupperman at Level Ventures, research done by Jordan Nel and team at Nomads and Hummingbird VC, and writings by Heather Hartnett of Human Ventures.

really great piece Scott.

(and I LOL’d at the story about investing in global pre-seed... def heard that one b4! ;)