Overton Windows in Venture Capital

How policymaking and investing differ radically

People often ask me about my two experiences working in the White House, and its relevance to venture capital. I’ve had a pretty unique chance to see both a Republican and a Democratic administration within the highest levels of the West Wing, and reflect on these experiences over the last decade as a venture capitalist. I’m fortunate to have spent five years at the Council on Foreign Relations as a Term Member, an experience I often recommend to technology and VC peers who have an interest in assembling a more holistic worldview across capital markets and government. There are other great programs like Milken YLC, or Aspen Crown Fellows, as well.

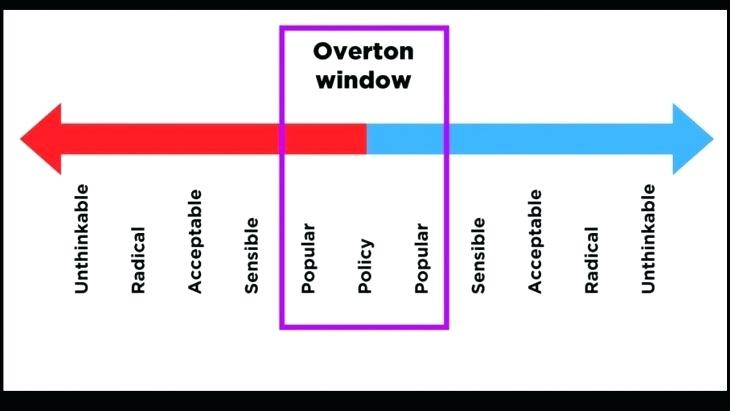

In policymaking what’s interesting is that you’re often trying to cross the aisle and find middle ground. You’re trying to draft consensus ideas that appeal to a broad base. Many are familiar with the term “Overton Window,” which describes a current spectrum of policy options to which society is open. As policy choices polarize in opposing directions they move from “popular” to “sensible” to “acceptable” to “radical” to utterly “unthinkable.” Of course, what’s interesting in venture capital is that it’s the exact opposite. If you’re seeking alpha as an investor, and you’re considering the spectrum of consensus thinking, you’re seeking to identify the Overton Window, and then seeking to spot a dislocation where you think society is wrong, and you are right. That’s what it means to be contrarian. You have to take the position that is deemed radical or even unthinkable by others, and be correct. If you’re investing in ideas that are sensible or acceptable, you’re playing it safe.

As a founder this is also a great way to form a thesis around a radical idea. If you’re explaining the premise for your company or vision, it might help to frame it in a way that first explains the concept in the parlance of modern consensus and acceptability. Where is the Overton Window for what you are doing? What is consensus, and what is the breadth of acceptance around the consensus? Narratively framing what you are doing within the scope of acceptability will engender “buy-in,” but then providing the “twist” or the radical departure will allow you to differentiate the lemmings from the visionaries who should be on your team. I call this “Vanilla with a Twist.”

In the early days of Google Docs there were twenty features that differentiated Google Docs from Microsoft Word, yet the sales team struggled to get companies to adopt it. What they discovered was that the best sales tactic was to describe Google Docs as “exactly like Microsoft Word, except for…” and then only articulate one key difference.

That key difference ended up being cloud collaboration, or the idea that you could have “multiple people in the document at the same time.” No one needed to hear the other 19 differentiating features. In fact, by listing more features, buyers would find fault with one and that would torpedo the deal and adoption. By keeping the pitch laser focused around “plain vanilla with a twist,” highlighting only one key difference, they honed in on why people wanted to adopt Google Docs over Microsoft Word. What they were doing was pitching within the Overton Window, plus one additional detail and key difference that made it both radical, but also understandable.

Similarly a great pitch speaks to the middle of the aisle, the middle of the Overton Window, by saying “everyone else is doing this. We agree with this, except for one thing. We do that, and that makes us radically different. Crazy even.” You’ve just spoken the language of the middle aisle, and then expressed your radical departure. If those you’re pitching don’t go with you to this frontier of contrarianism that’s fine. You’re self selecting for the people who get your vision. You’re taking a swing. You could be incorrect, but the only way to win is to be contrarian and right. People who don’t intellectually go with you to this frontier either think you are wrong, or they are too mired in consensus thinking to be your long-term partner. Identify the Overton Windows, and then depart from them radically. Chase the frontier, and find your people. Unlike policy you don’t need to win the masses. You need only win a few.